|

|

|

| Brugge / Bruges | |

| Here are some pictures from our trip to Bruges in March 2002. The history of Bruges begins around 2000 years ago. At that time there was a Gallic-Roman settlement on the site of the city. The inhabitants did not live by agriculture alone, they also traded with England and the rest of Gaul. Around 270 the Germanic people attacked the Flemish coastal plain for the first time. The Romans probably still had a military fortification here at the end of the third century and during the fourth century. So it is very possible that Bruges was inhabited in the transition period to the early Middle Ages. When Saint Eligius came to spread Christianity in our area around 650, Bruges was perhaps the most important fortification in the Flemish coastal area. |

|

|

The old market square of Bruges |

|

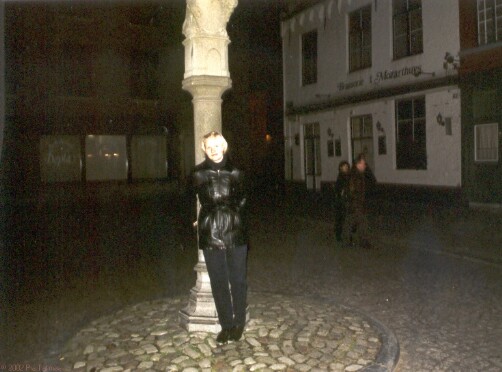

| Bruges by night. So Bruges has a long tradition of international port activity. The oldest trade settlement of Bruges and the early middle age port was accessible from the sea until around 1050. The second area of occupation outside the Burg was close to the present day Steenstraat and the Oude Burg. It was here that the city grew fastest until around 1100. The two oldest parish churches in Bruges, the Church of Our Lady St.-Saviour's, were then at the edge of this district. They date from the ninth century. |

|

|

Famous lace making in Bruges. In the eleventh century Bruges had expanded to become a commercial centre for Europe. But during this period the natural link between Bruges and the sea silted up. A storm flood in 1134 changed the appearance of the Flemish coastal plain however. A deep channel appeared, the Zwin, which at the time reached as far as present day Damme. The city remained linked to the sea until the fifteenth century via a canal from the Zwin to Bruges. But Bruges had to use a number of outports, such as Damme and Sluis for this purpose. Creating handmade bobbin lace is a time-consuming craft that requires patience and good eyesight. Mìeke Lams, left, whose grandmother was a lace maker, demonstrates the technique inside her shop, Lace Jewel near Market Square. A small handkerchief takes about 30 hours to make. Few tourists are willing to pay the price for authentic Belgian lace, says Lams, the reason why many of the shops in Bruges now also stock cheaper imports. |

| The belfries of Bruges. So in the Middle Ages it was possible for Bruges to become the most important trade centre of north-west Europe. Flanders was then one of the most urbanised areas in Europe. Flemish cloth, a high quality woollen material, was exported to the whole of Europe from Bruges. From the thirteenth to the fifteenth centuries Bruges had between 40,000 and 45,000 inhabitants, double the number now in the historic inner city. In the fourteenth century Bruges had expanded to become a rich international port city. Merchants from northern and southern Europe came together here. For their business they used Bruges brokers and landlords. In the city itself there was not only Flemish cloth manufacture but all kinds of other (craft) trades had developed. It is significant that in Bruges at that time there were already real bankers in operation, both natives of Bruges and Italians. Merchants could open a current account here, transfer large sums, change money and even pay with notes. |

|

|

The canals of our fair city. But we should not forget that hard times also occurred regularly in Bruges. The differences in income between the ordinary people (the tradesmen) and the merchant entrepreneurs (the patricians) were huge, regardless of those in the middle. Violent revolts, like those of 1280 and 1436-1438 were roughly suppressed. In the 1302 uprising the ordinary people took the side of the Flemish count against the king of France and the propertied classes. This struggle, in which Bruges played a prominent role, resulted in a victory for the tradespeople and the Flemish count in the Battle of the Golden Spurs on 11 July 1302. This historic date is now the feast day of the Flemish community in Belgium. The fourteenth century, a period of crises for Bruges and Flanders with revolts, epidemics, political unrest and war, ended with the dynastic merger of Flanders and Burgundy. The Burgundian period in Bruges started in 1384. Bruges would remain the most important trade centre to the north of the Alps for another century. Cloth production was partly replaced by luxury goods, banking services, crafts. The Burgundian court provided a great deal of local purchasing power. This was promoted further by the foreign merchants with their international contacts from Portugal to Poland. Prosperity increased, travellers came and were deeply impressed by the sumptuousness and luxury of the city scene. Art and culture flourished as never before. But all this came to an end with the sudden death of Mari of Burgundy in 1482. The revolt against her widower Maximilian of Austria meant that Bruges suffered political uncertainty and military force for ten years. Local prosperity disappeared from the city along with the Burgundian court and the international traders. |

| The belfries again from an other point of view. In the sixteenth century Bruges recovered to an extent. But the city had clearly lost its leading position to Antwerp. However Bruges remained important as a regional centre with a lot of international commercial contacts and a flourishing art sector. The split from the Netherlands, final from 1584, led to the final decline of Bruges. Around 1600 Bruges was a provincial city with a modest maritime reputation. The Bruges merchant spirit had still not disappeared in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Commercial life had international roots. Bruges shipowners and merchants still traded with the Spanish empire, England and the East and West Indies. |

|

|

The 'Burgh' taken from top of the Belfries. With just 22,000 residents in the historical center, Bruges draws more than 3 million visitors annually, most of them Europeans who come on day trips. But Bruges has enough museums, historical sites, walking paths, restaurants and cafes to keep a visitor occupied for a few days. It's an ideal destination if you're looking for a low-key place to relax in between visits to Paris and Amsterdam, and it's a good base for visiting Brussels, Ghent or Antwerp. Bruges has more than 100 hotels and numerous B&Bs, so finding a room usually isn't a problem, but advance reservations are recommended. Weekends, May through October, are the busiest times. |

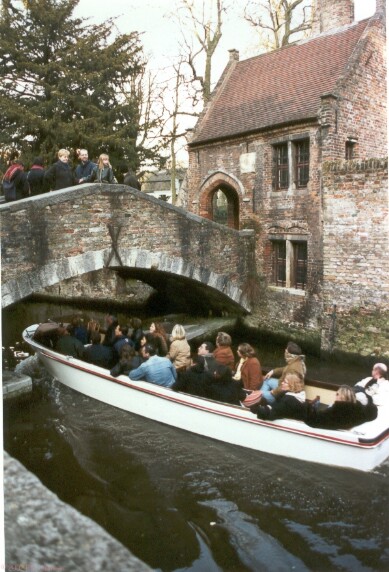

| The smallest bridge of Bruges. Getting there: Bruges is 60 miles west of Brussels. Frequent trains from the capital to Bruges take about an hour. Trains from Amsterdam take about three hours, from Paris, about 2-1/2. General information: Toerisme Brugge, Burg 11, Bruges, is a one-stop source for information on Bruges, lodging, museums, restaurants and Bruges2002 events. See the Web at www.bruges.be or phone 011-32-50-44-86-86. Information is also available from the Belgium Tourist Office at www.visitbelgium.com or by calling 212-758-8130. |

|

|

And this is the oldest bridge... Lodging: Bruges brims with hotels, youth hostels and B&Bs. The most atmospheric are the smaller places in historic buildings. Travelers with disabilities should inquire about access. Many buildings have steep staircases and no elevators. I chose Dieltiens B&B, Wallsestraat 40, in the city center a few minutes walk from Market Square. Prices range from - per night including breakfast for one person to - per night for two persons. For reservations, see the Web at users.skynet.be/dieltiens or phone 011-32-50-33-42-94. The tourist office Web site, www.bruges.be, includes a comprehensive lodging list including prices, phone numbers and e-mail addresses. |

| The townhall. We walked in morning sunlight to the Markt (Market Square), the central plaza lined with cafes inside gabled houses ringed in colored lights. I could hear the clomping of the horses that carry tourists in carriages along cobbled streets. Later, I'd climb the 366 stone steps to the top of the 800-year-old belfry. But for now, I was content to see Bruges at ground level. We strolled along the Dijver canal across a stone bridge to Mariastratt, passing the spired 13th-century Church of Our Lady that houses Michelangelo's white marble Madonna and Child. We came upon whitewashed Alms houses, cottage-style apartments with flower gardens and window boxes, maintained by wealthy merchants during medieval times for the poor and aged, now owned by the city to provide housing for older residents. And we met Sylvia De Boey, 69, who invited us in to see her rooms inside Godshuis De Meulenaere, an Alms house with the date 1613 stamped into her stone fireplace. We drank "Strong Henry," the local beer named after five generations of men named Henry, and sipped hot chocolate at a table set with saucers of melted chocolate and pitchers of steamed milk. |

|

|

Nice is'n it? Egg-shaped Bruges, with a historical center encased within a moat that follows the city's medieval fortifications, is small enough to walk around in a few hours. It is among the most perfectly preserved cities in Europe, but it yearns to be seen as more than just a medieval theme park. "A lot of people consider Bruges as a kind of open-air museum," says Geraldine Leus, a member of the Bruges2002 staff. "They come here on big buses and make Bruges a quick stop. They see the faces of the buildings, but they don't really see what's behind them." |

| Bruges in all her glory. Eating and drinking played a big part in Bruges history, so much so that the tourist office has designed a self-guided walking tour around the theme. In modern-day Bruges, dinner can be an order of Belgian frites from one of the street kiosks ($1.30 for a heaping plastic tray, plus 35 cents extra for mayonnaise); a platter of steamed mussels served fireside at one of the tourist restaurants in the gabled guildhalls on Market Square, or a simple platter of cheese at a beer cafe such as the De Garre. With its heavy wooden tables and 300 kinds of beers, the De Garre feels more like a wine bar than a tavern. Belgians take their beer seriously, and the cafes are where friends gather to talk or play cards. Most are family places. A stash of board games in the corner is a clue that children are welcome. "Belgians sip their beer slowly," our waiter told me. I ordered a golden wheat beer called witbier brewed with orange peel, coriander and other spices. Like all Belgian beers, it was served in the local brewery's signature glass. |

|

|

Market square from the air. Behind the scenes Most of the historic sights lie in a compact, walkable area between the train station and Market Square. But there's much more to explore, especially at night when the tour groups leave and the lights come on, bathing the canals and warm brick buildings in a yellow glow. "Most tourists stick to the city center, but if you walk just a half-block in another direction, you'll see a part of Bruges you wouldn't expect to find," says Dirk Cleenwerck, 37, a Bruges native who designed an online walking tour of the city. His advice: Put the guidebook away and amble. He and I met one evening at the De Garre, a beer cafe in an unmarked alleyway between Market Square and the Burg, the site of the town hall where the iron rings on the wall were mounted not to tie up horses, but to hold prisoners. |

| Punisht and put at the pool. Big year planned With its designation as one of two European Cultural Capitals for 2002 (the other is Salamanca, Spain) by the 15-nation European Union, the city will host 160 concerts, art exhibits and other cultural events, from a major showing of the works of Flemish artist Jan van Eyck to live theater performances inside the town prison. The events are likely to mean Bruges will be more crowded than usual, especially during summer weekends when the "streets are so packed, you can hardly walk," says Jean-Pierre Drubbel, the city's tourism director. But, he says, "the majority are day-trippers," who make Bruges a quick stopover on their way to or from Brussels, Paris or Amsterdam. |

|